“For the most part, our lived experience has been that we have not been heard,” she said.

“As soon as governments interfere with our right to decide how we are represented, our voices become muffled, confused, and ultimately silenced.

“Governments have made promises, commissioned reports, initiated multiple inquiries, and still failed to produce an outcome.”

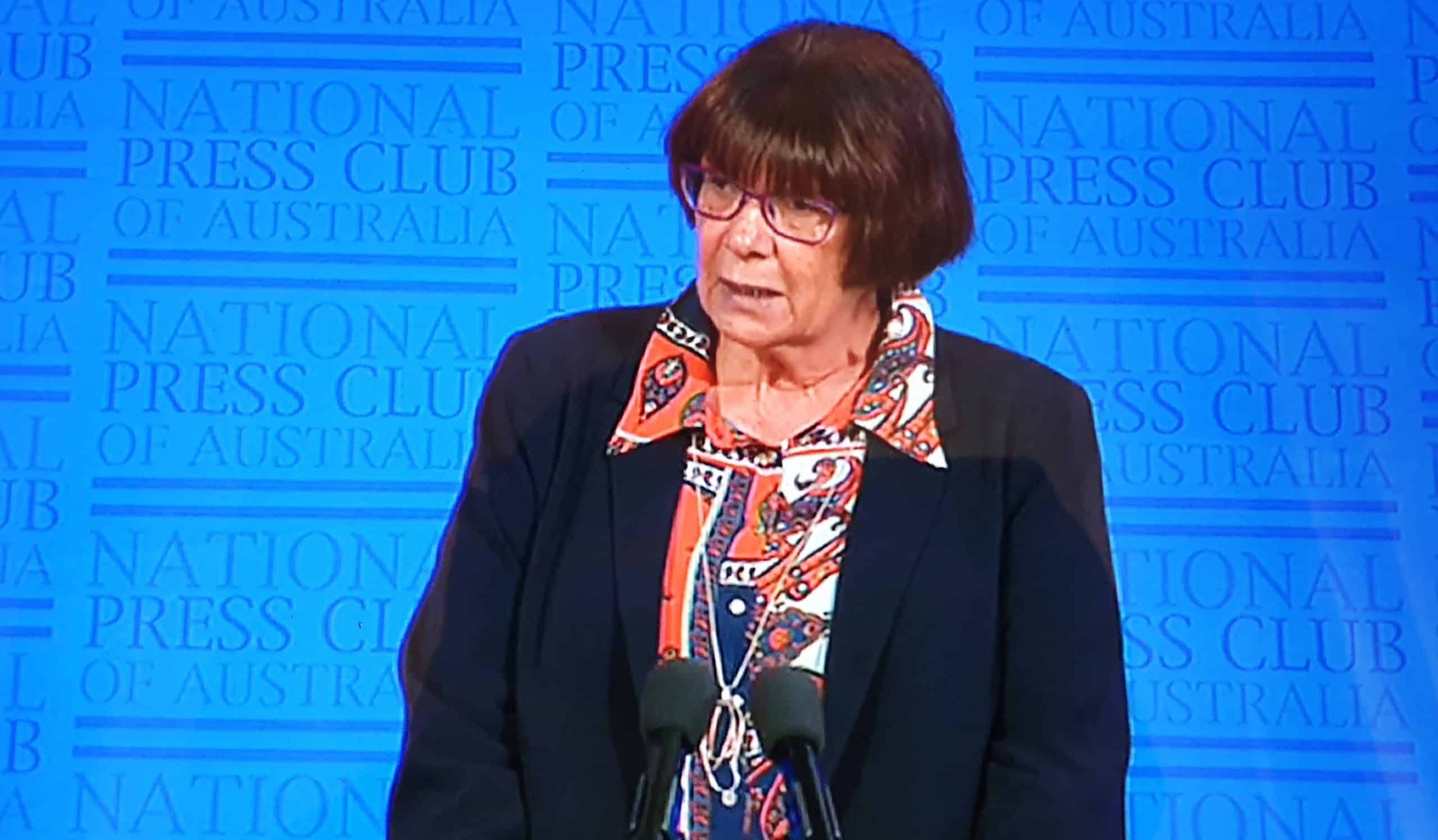

Turner is the chief executive officer of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation and one of 19 members appointed by the Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt, to a senior advisory group providing input on the Voice’s “co-design”.

With permission, Pat Turner’s speech is published in full below.

The Long Cry of Indigenous Peoples to be Heard

Indigenous peoples across the globe share similar histories.

We share deep attachments to our land, our cultures, our languages, our kin, and families.

These attributes have developed over millennia to harmonise with the natural environment, manage and sustain natural resources, and to facilitate meaningful and healthy lives.

They reflect core values that have served us, and the wider world, remarkably well.

Indigenous peoples also share histories of colonisation, violent dispossession, overt and disguised racism, trauma, extraordinary levels of incarceration, and genocidal policies including child removal, assimilation, and cultural and linguistic destruction.

These histories were — and are — real and alive, both in the way we see the world and in the political and social structures that have been imposed upon us.

In last year’s Boyer Lectures, Rachel Perkins quoted the poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal: ‘Letno-one say the past is dead. The past is all around us’.

And Rachel cited her father, my uncle, Charles Perkins, who would say: ‘We cannot live in the past; the past lives in us’.

In other words, we cannot forget the past. We all must work to make sense of it, to come to terms with it.

We must work to overcome the inter-generational consequences that are all too real for so many Indigenous peoples.

In his 1968 Boyer Lectures, anthropologist, Bill Stanner, identified the propensity of non- Indigenous Australians to not see, to forget, and to actively disremember the consequences of colonisation.

He termed this ‘the Great Australian Silence’. What he didn’t say, but it was inferred, isthat this structural silence necessarily means also shutting out Indigenous voices.

Four years later, Stanner quoted Dr Herbert Moran, surgeon, medical innovator, and first captain of the Wallabies, who wrote in 1939:

We are still afraid of our own past. The Aborigines we do not like to talk about. We took their land, but then we gave them in exchange the Bible and tuberculosis, with for special bonus alcohol and syphilis. Was it not a fair deal? Anyhow, nobody ever heard them complain about it.

Nobody ever heard them complain about it!

Of course, we know now that there has been a long history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander complaint, protestation, resistance, resolve and repudiation.

Two hundred and fifty years ago, Lieutenant James Cook ordered his sailors to open fire on two remonstrating Gweagal men as he came ashore.

From that day to the present day, courageous Indigenous men and women have sought to be heard regarding the ownership and meaning of this land and the rights of its First Peoples.

Pemulwuy, Yagan, Multeggerah, Truganini, William Cooper, Bill Ferguson, Eddie Mabo,Charles Perkins, Jack Davis, Lowitja O’Donoghue, and others confronted and broke through Stanner’s Great Australian Silence.

However, for the most part, our lived experience has been that we have not been heard. Hearing us involves more than merely being allowed to speak.

It involves more than merely listening.

It requires respectful engagement, two-way communication, and ultimately action.

It requires the non-Indigenous majority — most importantly governments — to act on what they have been told, and to explain their actions in response.

It is the essential ingredient in shared decision-making of policies, of programs, and crucially it is the essential ingredient for our self-determination.

Pat Turner, CEO of NACCHO and Lead Convenor of the Coalition of Peaks National Press Club, says, “we are at a critical juncture.” Picture: Supplied.

Australia in the World

How should we assess Australia’s comparative performance?

If we take as our measure the response of governments in other liberal democratic nations with Indigenous minorities, we are lagging.

While cross-national comparisons are far from straight forward, it is fair to say that the institutions and structures that allow Indigenous peoples to be heard are much better developed in these nations than in Australia.

In Canada, section 35 of its Constitution recognises the inherent right of Indigenous peoples to self-government.

There are currently 25 self-government agreements in operation across Canada. A further 50 or so negotiations are ongoing and in many cases are being negotiated in conjunction with modern treaties.

In New Zealand, the signatures to the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 was followed by its dismissal by the British colonists.

They failed and the Maori were not silenced.

The 1975 decision of the New Zealand Parliament to establish the Waitangi Tribunal reinvigorated the treaty process and led to a swathe of negotiated settlements and compensation packages. That process is ongoing.

In Norway, Sweden, and Finland, the Sami people have access to their own elected Parliaments, sub-national bodies with subsidiary functions to promote political initiatives for Sami and to carry out the administrative tasks delegated from national authorities.

The common feature of all these arrangements is to provide Indigenous peoples with structures that ensures they will always be properly heard by the relevant nation state.

The structures in these other nations do not, of themselves, resolve the differences between the dominant and the Indigenous peoples. But they do provide a mechanism where those differences can be articulated, considered, and ultimately addressed.

Australia does not have these mechanisms but should have.

Apart from the ethical arguments in favour of alignment with other liberal democracies, there is a further pragmatic reason for Indigenous Australians to be heard.

Australia is a middle power, a liberal democracy. We are fortunate to have an independent judiciary and a robust public realm where we debate ideas and are free to express a wide range of views.

Yet we face an increasingly turbulent and uncertain world, where global challenges such as climate change, deadly pandemics, and nuclear war are no longer unthinkable.

The strategic environment and our economic future appear to be in serious tension.

Populism and authoritarianism increasingly seem to be the default political response to uncertainty and flux.

In such a world, it is in Australia’s interest to present a politically coherent and ethical profile to the world.

We should seek, as Gareth Evans argued in the first lecture in this series two years ago, to advance our national interests through proactive global engagement, rather than a myopic focus on our backyard and more obvious bilateral interests.

I am firmly with Gareth Evans that our capacity to project influence and shape external events is to a significant extent a function of how we are perceived by the international community.

One of the most obvious and oft-used metrics is Australia’s racist past and its current treatment of its First Nations peoples.

The men, and they were all men, who drafted our Constitution overwhelmingly held views we consider racist today. Our Constitution was, and continues to be, a document built upon racist foundations.

How can we confidently raise concerns about human rights, whether it be the treatment of Uighurs in China, or the death penalty in Iran, or mass incarceration and police over- reach in the US, or the restraints on freedom of expression in Hong Kong, while failing to hear the cries of Indigenous Australians for justice, fairness, and equality?

In a world where the economic security of all Australians is dependent in large measure on our capacity to project influence and soft power, why would we tie one hand behind our back?

The struggle to be heard in Australia

Australia knows that there is unfinished business in relation to our First Nations peoples.

Since the early 1970s, every major institution established by government to hear First Nations peoples has been dismantled or hijacked by government.

When what we said became inconvenient or uncomfortable to the nation state, our voice was undermined, supplanted, or discredited, before then being abolished.

For many years now, the notion of Constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians has been front and centre in national political debate.

Governments have made promises, commissioned reports, initiated multiple inquiries, and still failed to produce an outcome.

In 2017, we marked the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum which had withdrawn two adverse references to my people in the Constitution.

That same year, following extensive Indigenous led engagements with Indigenous communities across the nation, Indigenous peoples developed the proposals outlined in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

It proposed a constitutionally entrenched mechanism, a Voice to Parliament on laws about my people.

It was a mechanism to facilitate engagement, dialogue, and discussion between those so far excluded and those who are elected to make laws for the people of Australia.

The response from government was, once again, not to hear our cry.

This treatment merely serves to reinforce and confirm the torment of our powerlessness, to borrow a phrase from the Uluru Statement.

We were not and have not been heard. But we persist. We always do.

In late 2018, a group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled peak organisations – covering health, legal services, child protection, native title, land, disability, healing and education – joined together to be heard on Closing the Gap.

Closing the Gap is the headline government policy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, initially agreed only among Australian Governments in 2008. Its aim is to achieve equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with other Australians.

It is a policy that governments say is for us, about us, but until now we have had no formal way of having a genuine say and being heard.

We were deeply unhappy with the way that governments were proceeding with what they termed a ‘refresh’ of the Closing the Gap policy in 2016.

Governments said they were consulting with Indigenous people across Australia about this next phase. But we could not see that our views had been taken account of in the government proposals.

Governments were still making decisions about us, without us.

To his credit, Prime Minister Scott Morrison heard us. He agreed that we needed an urgent and different approach.

Without strong and public leadership from a Prime Minister, the task for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be heard is that much harder, nearly impossible.

The Prime Minister led the Council of Australian Governments, as it was then, to agree to a formal partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled representatives to share decision-making on Closing the Gap.

We formed the Coalition of Peaks. That Coalition now has over fifty Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders community-controlled member organisations spanning our key interests across the country.

This is a significant point. Indigenous Peoples formed the Coalition of Peaks, on our terms, as an act of self-determination.

We decide our own membership criteria, we set our own rules for how we operate and make decisions, and we have our own secretariat that is accountable to us, providing policy advice furthering our interests, not that of governments.

None of the Coalition of Peaks members or the people who are at the table, sit as individuals. We are accountable to our boards and our members, and we act in their interests.

We were not chosen by nor are we accountable to government.

I say this is a significant point because it is a critical precondition for Indigenous peoples being heard.

We must choose who speaks for us, how and on what issues.

As soon as governments interfere with our right to decide how we are represented, our voices become muffled, confused, and ultimately silenced.

Together with all Australian governments, including local government, the Coalition of Peaks negotiated two vitally important Agreements, committing governments to change the way they work with us so that we can be heard.

This is the first time that intergovernmental agreements have been agreed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives.

The Partnership Agreement on Closing the Gap, which commenced in March 2019, and cements the partnership agreed to by COAG.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap which was negotiated under the Partnership Agreement and was launched on 30 July this year by the Prime Minister and me.

The National Agreement does not include everything the Coalition of Peaks wanted, nor everything our people need. It was a negotiation after all.

However, it does include historic commitments that go to Indigenous peoples being heard.

First, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap extends the shared decision-making principles of the Partnership Agreement and applies the commitment to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on all policies and programs that impact on us.

It is a commitment to Indigenous peoples being heard through a series of formal partnership and shared decision making arrangements, where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people choose our own representatives and operate in accordance with our own internal governance structures and are supported to have our own independent advice.

The second important commitment of governments relates to strengthening the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled sectors to deliver services and programs to our people.

It is increasingly accepted that our community-controlled organisations get better engagement, deliver better outcomes and employ more of our people.

What is less understood is why.

It is because our own community-controlled services hear us.

Our own services are designed by us, to hear our needs, and act on our solutions.

The community-controlled sector is built on Indigenous people being heard.

Third, the National Agreement also includes new levels of accountability on governments and a high degree of transparency for the way they work with us.

Because the way governments work with us is critically important.

It has not been an easy road to reach consensus on the National Agreement on Closing the Gap between governments and the Coalition of Peaks.

But the way that we have done it means we have had the opportunity to be heard.

Risks to being heard

Serious risks to our being heard still lie ahead.

The Partnership and National Agreements provide a platform for a new era in Indigenous Affairs based on genuine partnership in decision making.

It is early days though. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap still has to be implemented.

And words are never enough.

In the meantime, there are several high-profile instances where Indigenous voices are still being ignored, set aside, and not heard.

The recent decision by Rio Tinto to destroy the caves at the Juukan Gorge, and the failure of both the Western Australian and Commonwealth governments to protect this site of international significance continues to reverberate.

Protesters support Indigenous people and the Black Lives Matter movement at a rally in Sydney in June. Picture: Jacky Zeng.

While the Senate inquiry is welcome, Indigenous peoples are yet to be provided with a convincing explanation of how and why our voices were ignored – not just by Rio Tinto but also by the responsible Indigenous and non-Indigenous cabinet ministers.

That site, like so many others, is now gone. It cannot be replaced.

The pain and suffering are magnified because those landowners responsible for the country were not heard.

While the Western Australian government is reviewing its legislation, there is no formal way for Aboriginal people to be heard properly and to share decisions on a draft Bill to protect our heritage

Aboriginal people are being treated like any other stakeholder and on a similar basis as the mining industry but without the resources or political clout that the mining industry has in its dealings with governments.

The next key example is the Commonwealth government’s latest response to the cry for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

It is high on rhetoric and well-rehearsed: co-design, empowerment, doing things with us, rather than to us. But if we look closely, the practice continues to be poles apart.

After the initial rejection of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, what is now unfolding is a convoluted and flawed process.

This process is based on advice being given to the Commonwealth government for it to decide on a model of a Voice.

It involves government selecting its own advisers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, three separate committees, including a Senior Advisory Group, with potentially overlapping roles, and terms of reference that impose limits on wider discussion by participants.

I am one of those individuals appointed to the Senior Advisory Group.

That we are there as individuals – not representing or accountable to our own constituencies, organisations, membership or cultural groups – appointed by the government – to support the Minister – immediately compromises the strength of our voices, of us being heard as Indigenous peoples.

The secretariat support for the groups – steering the process – is provided by the Commonwealth National Indigenous Australians Agency, which is accountable to the government.

It is important to note that these arrangements are not consistent with the commitments from governments to shared decision-making in the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

Another clue in the shortcomings is in the name: the Senior Advisory Group.

Its job is to provide advice to government and this is not shared decision making.

Co-design and shared decision making are not the same thing, and giving advice and shared decision making are very different things.

It is true that the Minister for Indigenous Australians has committed publicly to an engagement process with our peoples and other Australians on models for the Voice.

But the options that will be put for a national conversation will be decided by the government, not by us.

How our Voice is heard must be properly negotiated between government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives, who are agreed by us.

As it is currently proposed, final decision making on our Voice is to occur behind closed doors by government.

There is also the matter of the scope of the government’s proposed Voice.

The model of a Voice being envisaged by government is not one that is constitutionally enshrined, not one that would speak to Parliament and is unlikely to be based in legislation.

It would be a Voice that speaks to government.

How this intersects with the partnership structures set up under Closing the Gap and will work with the now well-established role of the Coalition of Peaks is not clear and needs to be openly discussed.

It is also not clear, and needs to be openly discussed, how another Voice to government will intersect with the roles and relationships of our already many voices to government, that have been established over decades, and strengthened since the demise of ATSIC.

This includes Land Councils, the National Native Title Council and Representative Bodies and other community-controlled peak bodies, like NACCHO and SNAICC – national voice for our children. It also includes the many regional governance models that have been established.

What will happen to these dedicated, expert subject matter, and regionally based voices? Will government get to pick and choose whose voice it listens to, when and on what, leading to a silencing of some.

A compelling case for shifting away from a Voice to Parliament to a Voice to government has not been made. It was a decision by the government, and we were not asked or involved.

Whether intended or not, the outcome of the government-controlled process for establishing a Voice is likely to be disjointed, conflicted, and thus counterproductive.

Most concerning of all is the risk of considerable division arising between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in respect to the government’s Voice – and this is unacceptable.

The lesson from past failures is that Indigenous peoples have to be able to set up their own structures to reach decisions in their own time about how they are to be represented.

In fact, no different to anyone else in our society, not having governments to decide the outcome.

That extends to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being able to negotiate with governments to agree on an outcome.

This has happened before in Australia, when the Native Title legislation was negotiated in 1993 and of course on the Partnership and National Agreements on Closing the Gap.

However, notwithstanding the new partnership being heralded, it is not happening in respect to the government led process for establishing its Voice.

I am reminded of my schooldays, watching boys kick empty cans down a dusty road in Central Australia.

The defining moment

My message today is that Australia has reached a defining moment.

The finalisation of the Partnership and National Agreements on Closing the Gap marks not an end point, but the start of a new journey.

The commitment to shared decision-making between government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is not to be applied only at the discretion of governments when, and on what governments determine.

The development of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament and laws designed to protect our heritage, should not be an exception.

The proposed Voice to government, like the many incarnations that have gone before, will not stand the test of time and be doomed to fail unless these foundational short comings are addressed urgently.

As I see it, to take that forward step we must address three key challenges.

The first challenge relates to the full implementation of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, which is binding on all governments.

The commitments within those Agreements require a complete overhaul of the way governments do business.

Governments need to re-imagine the way that they work with us, our organisations and communities.

They need to examine every aspect of their dealing with us and apply the binding commitments of the National Agreement.

Every policy proposal must start with the question: how does this meet the obligations in the National Agreement?

Anything less is a failure to deliver on the potential in the National Agreement. The second challenge relates to the proposal on a Voice.

The current process for its development must be redefined.

All options must be underpinned by genuine shared decision making between the government and Indigenous peoples.

We must always choose our own representatives. And those representatives must negotiate and agree with governments on a model that will give rise to our genuine voice.

Any model being weighed up must consider the current landscape of Indigenous representation and voice, including the developments on Closing the Gap.

The two challenges that lay before governments are not radical. They are not unreasonable, particularly when compared with the institutional arrangements that exist in comparable liberal democracies.

The third challenge is to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It is a challenge I apply to myself.

To seize the opportunity in front of us, we must act in our collective interests.

We must demand that governments apply the commitments in the National Agreement on Closing the Gap to all its interactions with us, our organisations, and communities.

A benchmark of shared decision-making has been established in the National Agreement.

We must only engage with governments when they demonstrate they are prepared to meet it.

We are the best form of accountability, and we must hold governments to account.

In considering how we take forward the government’s proposal for a Voice, we mustopenly debate the options in front of us.

The National Press Club in Canberra.

We cannot be single minded, rejecting or talking down the efforts or ideas of others. A pursuit of a singular vision will only limit what is possible.

Anything less will leave us vulnerable to a short-term structure that can be dismantled following an election or the receipt of uncomfortable advice.

We are at a critical juncture.

As a nation we face many challenges, but one of the more significant relates to how First Nations peoples are acknowledged and heard.

If you have truly heard me today, as an Aboriginal person, some of the things I have said will be difficult and should challenge you.

I am not here to make you comfortable. Change does not happen when we are comfortable.

It is also not comfortable for me. The life of an Indigenous person, struggling with the cry of our people to be heard, is not an easy one. And speaking out is rarely received by applause.

My uncle, Charles Perkins, who was also my mentor, never lived a comfortable life.

Charlie was a fearless spokesperson. He said what needed to be said, at the time it needed to be said.

His life was uncomfortable, and he made all Australians uncomfortable.

But progress was made because all of us were prepared to listen and respond.

We need to do the same now in facing the challenges and opportunities that are before us.

We need to apply the new benchmark that has been set on Closing the Gap and extend it to how we respond to the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

If First Nations peoples are not able to be heard, Australia will continue to be diminished at home and in the world.

0 Comments