Last week the NT Coroner concluded his inquest into one of the Territory’s most intriguing unsolved mysteries, that of the disappearance of Paddy Moriarty from the tiny town of Larrimah.

The coroner ruled Paddy dead and referred the matter to the Director of Public Prosecutions, saying his death was most likely due to foul play related to his relationships in the town.

The NT Independent had reports from the inquest all week by Territory journalists Kylie Stevenson and Caroline Graham, who published a book late last year examining the disappearance of Paddy and the role the mysterious little town of Larrimah played in the whole saga – the place made up of a dozen or so folks “who mostly hate each other” but that once bustled with thousands of residents.

Here’s a republished excerpt from their fascinating book:

Read an edited excerpt from the book Larrimah:

It’s almost 500 kilometres from Darwin to Larrimah and people say there’s not a lot to see, but we see plenty. Sixty-eight termite mounds dressed up like people—one in a Santa hat, another in soggy old jocks. One dead pig. Eighteen dead wallabies and two live ones. A broken-down car with all its wheels stolen. Dozens of roadside memorials.

We speed past a tree with hundreds of shoes tied to it, signs about alcohol restrictions, flood markers stranded in the dust, lots of questionable accommodation facilities all calling themselves ‘resorts’. The scrub on one side of the highway is burnt black, like someone has tried to match it to the bitumen. Scavenger birds pick at roadkill.

We’ve seen no one else driving south, and only a handful of cars travelling north. At one point, the odometer stops working, and then it starts going backwards. Somewhere between Mataranka and Larrimah, a whirly-whirly appears, like an angry god has cast a tiny dusty tornado into our path. It’s hard to pretend it doesn’t feel like an omen.

Paddy Moriarty and his dog, Kellie, went missing at the end of 2017.(Supplied)

It is 2 April 2018. Paddy’s seventy-first birthday would have been three days ago. He’s been missing for more than three months.

The town appears like an absurd oasis on the dusty horizon. After a long stretch of scrub, it’s an assault of red earth, green palms, magenta bougainvillea. But an oasis is supposed to be an idyllic escape and, up close, Larrimah is not.

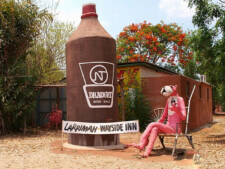

We follow some beat-up billboards with Pink Panthers on them—mostly hand-painted, and not always perfectly proportioned—directing traffic towards the pub, although the town’s handful of streets present very little opportunity for a wrong turn. Plus, the pub—commonly known as the Pink Panther—is easy to find because it’s painted bright pink and has a giant beer bottle out the front.

If it’s possible for a place to look hungover, the Larrimah Hotel does. It’s clear something wild happened here—some huge, eras-long party. But it’s also obvious the party is over, and the after-effects are showing. Everything is haggard.

For the past twenty years, Larrimah has been one of those few-and-far-between places on the highway that people either sped past or briefly stretched their legs in. But in World War II, thousands of soldiers were stationed here. The region had a picture theatre, a bakery, an ice factory, a railway station and a racecourse, and people reckon part of the war in the Pacific was directed from the verandah of the pub. There was a time when Larrimah mattered. Once the war ended, Larrimah ticked on as a wild, lawless frontier town—a transport hub, the end of the railway line, where people passing through met for beers that turned into days-long benders. At one point, there were three venues with liquor licences and often the pub was so busy you couldn’t get a parking spot.

Today, there is no such problem. We are the only car pulled up in front of a couple of oversized Pink Panther sculptures. One is headless, flying a gyrocopter, and the other is reclining in a deckchair.

There must be a line between a town and a not-town, but deciding where to draw it is tricky. When you google the smallest town in Australia, Cooladdi comes up. It’s in north-west Queensland and has three residents, but on closer inspection, it turns out they’re all related and run the local roadhouse, so it’s really more of a family business than a town. Betoota, in south-west Queensland, has tried to claim the honour, too, but its population has been zero since the owner of the pub died in 2004, which puts it firmly in ghost-town territory. Across the ditch, in New Zealand, a place called Cass says it’s one of the only one-man towns in the world. But really, when you’re down to one, you’re more of a hermit than a municipality.

With only twelve people—actually, eleven now—Larrimah is technically a hamlet. It has a handful of houses, an unmanned museum, a teahouse, a few sheds and, of course, the pub.

We cross the verandah of the Larrimah Hotel, past more stuffed Pink Panthers and old trinkets, and find ourselves face to face with Paddy Moriarty. He’s wearing a faded cap and a huge grin, which even his lush moustache can’t hide. He was known around these parts as a great storyteller; he was such a fixture that people called him the town concierge. But we don’t get the jolly welcome he’s known for. It’s only his face on a laminated sign under a huge headline: ‘Missing. What happened to Paddy?’

The police poster has all the grim details. Full name: Patrick (Paddy) Moriarty. Approximately 178 centimetres tall. Black and grey hair. Age seventy. Last sighted at dusk on Saturday, 16 December 2017, when he left the Larrimah Hotel on his quad bike with his dog, Kellie. She’s pictured on the sign, too—the red- and-brown kelpie looks young, friendly, with her tongue sticking out.

‘Hey, you girls need a hand?’ We spin around.

A man has appeared behind the bar, drinking a tinnie. We haven’t met him before, but we recognise him from the news stories about Paddy. His name’s Richard Simpson and we know he works at the pub. He’s got a long beard, he’s wearing a singlet with armholes so long and looping he might as well be shirtless, and his skin is so weathered you can’t make out the tattoo on his bicep.

But however rough Richard looks, he’s friendly. When we introduce ourselves as the latest mob of press to turn up, he shakes his scruffy head and is gracious about it. In lots of towns, buying a beer is the fastest way to prove you’re not an arsehole, so that’s what we do. Richard looks a bit relieved and cracks another for himself. The pace is slow in Larrimah, and we ease into conversation.

Where we’re from, what we’re doing. Small talk about the town. This is Richard’s fourth stint at the pub—he loves it. Says the place gets under your skin. But he admits it’s an acquired taste.

‘If you want five star, you know, clean with no dust, don’t stop at Larrimah, go somewhere else. Simple as that,’ he says. ‘We don’t need you coming in and whingeing at us ’cos we’re just going to take the piss out of you for it. It’s a country pub, you know. It’s one of the last ones left.’

We take that as our cue to finish up our beers and ask for the room keys.

‘You’re in room nine—the executive suite,’ he says, then steers us through the pub’s courtyard.

Caroline Graham and Kylie Stevenson,

The afternoon is thick with the sound of birdsong, made louder by the absence of any other noise. The courtyard is crowded with dozens of bird cages and plastic tables and chairs, shaded by sweet-smelling Rangoon creeper and a huge African mahogany. About ten paces from our bedroom door, we encounter the first of the pub’s three crocodiles: golden, at least a metre long, and missing its eyeballs. His name is Ray Charles but everyone calls him Ray-Ray.

‘He’s got a genetic abnormality,’ Richard says. ‘Not that there’s anything abnormal about genetics.’ He starts addressing the reptile. ‘Still just a little fella, aren’t you, mate? You old snaggletooth.’

As we unlock the room, there is a long, low rumble behind us.

The crocodile is purring.

It turns out, our room is called the ‘executive suite’ because it has two beds and the luxury of a toaster, in which some spiders have made a home. Everything is clean, but the hotel is fighting a losing battle against nature. An army of ants have taken over the en suite and the stench of bore water is overpowering. It smells like rotten eggs and the shower runs hot, even when you only turn on the cold tap. The only window is blocked off by an aviary of birds, casting a dimness over everything.

As daylight fades, the weight of why we are here begins to feel heavier. Paddy’s disappearance has heightened existing tensions in the town. Some residents are talking about leaving, and no one is young—health concerns are creeping up on people, and Larrimah is a long way from the nearest hospital. The place is slipping closer to the edge of extinction by the day.

It’s not just Larrimah. The outback is full of tiny towns struggling to survive and as they start to drop off the map, their stories, histories and ways of life disappear with them. You can almost see it happening, in slow motion.

Outside, dusk thrums with noises: birds, insects, the wheeze of the ancient box air-conditioner. We are a long way from anywhere, and Larrimah has no phone reception. It’s full of things that can kill you: spiders, snakes, crocodiles. Maybe people.

This is an edited extract from Larrimah by Kylie Stevenson & Caroline Graham (Allen & Unwin)

0 Comments